In Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych “The Garden of Earthly Delights” (1490-1510), the central panel depicts countless nudes enacting every imaginable fleshly pleasure. Yet something is off: Blind bacchanals happen inside hollow pieces of fruit that encase heads and torsos; one nude figure places a bouquet between the buttocks of another.

The same shadow of discomfort seems to hang over the rich visual profusions of Valerie Hird‘s “The Garden of Absolute Truths” — the title of both her solo exhibition at the BCA Center in Burlington and of one of the two animated videos in the show. Burlington-based Hird, an internationally recognized artist, counts Bosch among her many influences. The exhibition includes paintings, watercolors and painted cut-paper scenes, layered like pop-up books, that she has encased in wall-mounted mini theaters and freestanding peep box-like sculptures.

These delightfully imagined 3D constructions, referencing children’s tales and gardens, reward immersive scrutiny as much as does Bosch’s medieval triptych. They also encompass their own snakes in the Edenic grass.

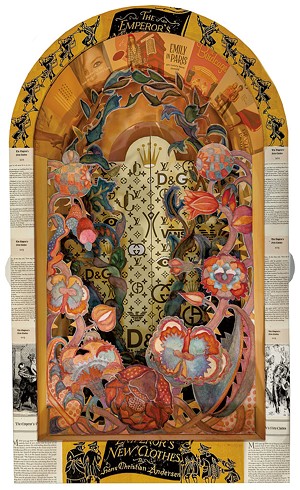

In “Gulliver’s Travels,” a girl facing down a large bear wears a dress emblazoned with the Ukrainian flag. In “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” a flowering arch partly obscures a pair of closed, arched doors patterned with today’s trendy labels, including Dolce & Gabbana and Vans.

Birds bearing the logos of Fox News, Twitter and Instagram fly through a magical, colorful landscape in “New Media”; you can turn a crank, fabricated by Michael Zebrowski, to make the flock go up and down. A pillar separating the tiny rooms and arched windows inside “Boxed In” is lined with a row of upside-down Facebook logos.

These are beautifully made objects, papered with text from the published stories to which some of the works refer. (Pages from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland with John Tenniel’s illustrations line the box frames of “Alice’s House,” also built by Zebrowski.) The works draw viewers into their narratives as fables draw in readers, while simultaneously destabilizing those narratives. As the introduction puts it, Hird’s work “reflects on the illusion, disruption and disarray within contemporary society.”

Even Hird’s abstract landscapes — gorgeous in their colors, composition and use of light — raise questions. “Flight,” a 22-by-44-inch watercolor, depicts a longitudinal desert landscape in which foregrounded mountains resemble the folds of patterned Eastern carpets. (The artist has spent time in the Middle East and North Africa, according to panels.) The three-dimensional coils of “Eternal Knot,” an oil on linen measuring 48 by 60 inches, have a similar ambiguity; they could equally be patterned ropes or a tangle of scaly dragon bodies.

“Origination I” and “II,” the exhibition’s largest paintings at 96 by 120 inches, set those multivalent coils within cloudscapes. The series explores “the endless cycle of matter and energy embodied in nature,” according to a panel. More ropelike shapes coil through “Source Code,” a series of 94 watercolors that are hung as a unit, each measuring 6 by 9 inches. And in “Seedlings I” and “II,” Hird develops her own iconography for young plant or tree growth: spirals of coils emerging from volcano-like cones.

The artist uses all these creations in her animated videos, which she made by scanning and digitally animating her work with the help of other artists.

“What DID Happen to Alice?” is Hird’s first foray into video, animated by Martin De Geus and edited by Max Ethan Miller. The 12-minute film uses Hird’s four “Alice” mini theaters (“Alice’s House,” “Transition,” “New Media” and “Boxed In”) as sets for an exploration of the artist’s identity through the character of Alice. The paper figure is flat but can show movement by bending and curling.

To a soundtrack composed and sung, murmured and trilled by Marshfield soprano Mary Bonhag, Alice progresses through different identities under the influence of different texts — including one in Arabic — that flow onto and cover her body.

“The Garden of Absolute Truths,” a less narrative video, was animated by De Geus and scored by Kara Gibbs. Using paintings, including Hird’s “Origination” and “Seedlings” series, the roughly six-minute short creates a mesmerizing creation story in the abstract — far from any absolute truth, the work’s title notwithstanding.

That word “absolute” encapsulates the most unsettling aspect of Hird’s exhibition, especially in a cultural moment rife with conspiracy theories and other intractable claims to “truth.” In medieval times, it was categorically a sin to give oneself over to carnality — hence the hint of hell in Bosch’s depictions of pleasure. According to Hird’s artist statement, today, “truth is a shapeshifter.” Her work, which she describes as a “comment on current power inequities,” is drawn from the steadfast moral messages of enduring children’s tales.